Two for One Read online

Page 3

By now we’d made so many turns and taken so many back doubles that I was thoroughly disoriented—if that’s the word I want, considering who was doing the leading. It also occurred to me to wonder if, perhaps, that wasn’t part of the point.

Although we didn’t see another soul, I was aware that there was plenty of other life on the planet. From behind thick wooden doors came the buzz and hum of people and machines at work. I was pretty sure that, should the need arise, legions of support troops armed to the teeth would pop up like mushrooms—or possibly toadstools. The thought of toadstools armed to the teeth gave me a moment of childish pleasure.

Finally, Charlie Chan came to a halt in front of a pair of double doors that were made of clouded glass. It was then that I recognized the sound that had been getting steadily louder for the past several hours we had been walking.

You know how you can be aware of the sound of the sea for quite some distance before you catch sight of it? Then suddenly you do and all the pieces fall into place and you can relax.

Well, this wasn’t the sound of the sea. This was the sound of all the birds in creation piping up at once.

“Welcome to The Aviary,” said our oriental guide. “You will find Mr. Kane within.”

And he opened one of the doors and stepped aside to allow me to enter.

Holmes and I moved into what was obviously an anteroom, for ahead of us was another pair of glass doors, misted on the inside. Even where we stood the temperature was significantly higher than the corridor outside and the condensation suggested the main room was even warmer but for the moment I could see nothing of what it contained.

Behind us there was a purposeful click. Mr. Chan was not going to accompany us any further. I just hoped he’d left a road map on the door handle, so that we could find the front door and the real world again.

Holmes was now at the far door and I had the distinct impression that it was only the inconvenience of my corporeal presence that prevented him from walking straight through it. But then patience had never been Holmes’s strong suit, I said to myself. And then I asked—but how do you know that?

Crossing mental fingers, I opened the door.

The sight that met my eyes is hard to describe unless, like me, you were brought up on a diet of boys’ adventure stories and hokey science fiction films. The closest I can come to it is to say that it was how Conan Doyle’s Professor Challenger must have felt when he finally got a look at that Lost World.

There were birds, birds … and then more birds. There were birds cawing, screeching and whistling on every surface in what I could discern as a virtual jungle of tropical trees and bushes. There were birds of every color of the rainbow and then some, most of them swooping and circling. There were even birds pottering about on the ground at our feet—though I noticed they gave Holmes a wide berth.

I stood there for a moment, wondering if I had somehow stepped into some state-of-the-art projection room and all of this was caused by special effects. At which same moment something plopped on my shoe. No, this was real, right enough.

“Over here, Mr. Watson.” The voice was metallic, amplified. “Turn right at the sago palm in front of you. And don’t mind my little friends. They can be a trifle playful at times but they mean no harm.”

A tiny green and purple creature underlined his point by darting at me and nipping me painfully on the ankle. I side-footed it, squawking, into a nearby shrub. I was brought up to believe it isn’t done to bite your guests, certainly not on the way in.

Sago palm—whatever that is—turn right … and there before me was a clearing in the jungle and in it, seated in a motorized wheel chair with a small table at its side, was the biggest bird I had seen in the aviary so far.

Osgood Kane—for I recognized him immediately, even though the rare photographs one saw of him in the press had clearly been taken decades ago—had become, as so many of us are fated to do, the thing that he beheld. In extreme old age he had come to resemble the birds he so clearly adored.

The body imprisoned in the wheel chair was that of a living mummy, but it was the face that caught the eye. Mr. Grypppe had aged into a turtle but Kane had turned into a vulture. The nose was beaky and—as Shakespeare said of Falstaff—“sharp as a pen”. The head was almost totally bald and the few remaining strands of white hair lay plastered flat against it, giving it a sleek appearance. The chin had disappeared into the wattles of creased skin on his neck.

Only the eyes were alive and the desiccation of the rest of him seemed to give them an unnatural brilliance. Bright and beady and missing nothing—including the mental evaluation I had just been making.

“Please take a seat, Mr. Watson. It was good of you to spare me the time in your busy schedule at such short notice.”

If there was a touch of irony in his tone, it was lost by the distortion of the sound of what he said. And then I saw the explanation of that metallic quality in his speech. Osgood Kane’s vocal chords had been removed. He was talking through a voice box. When he saw me looking, claw-like fingers fiddled with a small gadget on the side table.

“I must apologize for this inconvenient contrivance. When I wish to communicate with the rest of the world, I am forced to use it. Fortunately, I no longer wish to do so on anything but an intermittent basis. And, of course, I have the faithful Perlman to fetch, carry and occasionally bark for me. By the way, what did you do to him to make him so flustered yesterday? His fur was decidedly rubbed the wrong way.

“A delicate flower, Perlman …” The bright eyes were amused now. “He blows with the wind—and swings with it, too, I would guess. Though at this stage of the game even prurience loses its appeal. Always wears white, you know. Something symbolic there, don’t you think?”

He laughed and the amplified sound reverberated around the room, causing the birds to rise in the air as one. The noise was deafening. When it had died down a little, Kane whispered as confidentially as a man in that condition can whisper.

“You know, he hates to come in here. He’s afraid one of my little friends will do unto his precious white suit what one of them has just done unto yours!”

The shriveled hand went to the mouth as he enjoyed what was clearly one of his favorite jokes.

“Here,” he pushed a box of tissues across the table towards me. “The dear creatures are no respecters of person. I suffer my own share of their little tributes. But look at them. Are they not worth a little trouble for so much beauty?”

I thought this might not be precisely the moment for too much truth, so I contented myself with using the tissues.

“No, Mr. Watson …” The playfulness was now over and it was time for the matter in hand, whatever that was. “That is what I like about birds. They are their own masters in all the ways that matter. Free spirits. Unfettered by the too, too solid earth that claims us all in due time. But enough of philosophy which—as Keats reminds us—can clip an angel’s wings …

I have called you here because I want you to find a bird for me.”

“You don’t feel you have enough?” I looked up—carefully.

“I want you to find a particular bird. This bird …”

His hand went to a small cloth-wrapped package on the table next to him. Slowly and methodically he unwrapped what was inside and handed it to me.

I found myself holding an exquisitely-carved golden bird with its wings spread. It was about four inches across and about as long. And it was magnificent in every detail. It seemed poised as if about to take flight and at its feet were some wavy lines that might have been the artist’s representation of the branches of a tree.

And the eyes … somehow the sculptor or the artist or whatever he was had managed to convey the sense that the bird was looking right at you. The red eyes were every bit as beady as their owner’s but infinitely more malevolent.

And somehow the darned thing seemed to burn

my hands. The heat in the room was close to unbearable but this was something more. I handed it back to Kane like a hot potato.

“The Borgia Bird, Mr. Watson—unique and irreplaceable.”

“But you don’t need to replace it—you have it already.”

“Ah, if only … We collectors are strange birds—if you’ll excuse the execrable pun, Mr. Watson. We want to own something unique and, if no one else in the world ever sees it again, it only adds to the pleasure. So we will squirrel it from the light of day, take it out occasionally at dark of night to gloat over it, then hide it away again. A form of madness, no doubt, but a well documented one and divine madness, as I can attest. The Bird has been my own form of dementia these many years.

“But perhaps I should give you a little of its background, so that you will understand better what I seek and why.

“The Borgia Bird is so known in the world of antiques because it ‘fell into the hands’ of Cesaré Borgia around 1502. Which almost certainly means that whoever owned it at the time was summarily dispatched. Cesare gave it as a present to his sister, Lucrezia, with whom he was incestuously involved. After the dissolution of that feral but undoubtedly fascinating family the Bird’s history is cloudy. Over the centuries it seems to have passed from hand to hand, usually leaving blood on those hands.

“Many years ago—at a time when I was myself living in Europe—it passed into mine and I have been its guardian ever since …”

“Until now?”

“Until now …” Kane seemed lost in his own thoughts. “It is an objet without price, Mr. Watson. Think of the things it has seen, the places it has been. Even to touch it is to share a little of all that.”

Then he seemed to return to the present.

“I confess the Bird became something of an obsession with me—a conduit of sorts to other, more exotic worlds. As you see, I have become a prisoner in my own body.” The clawed hand gestured towards the skeletal frame in its confining wheelchair.

“I dared not exhibit it for fear of theft, yet I could not bear to be without it. And then I had what seemed to me at the time a brilliant idea. I would have a replica made, so that I could have my bird and hide it, so to speak. I had come across a man who had provided me with the occasional little objet and he happened to be a superb craftsman. He also happened to be corrupt enough that money would buy both his talent and his silence.

“To cut to the chase, as you Americans are so fond of saying, this man made me my replica and it was a brilliant replica, as you may see …” He weighed the golden bird in his hand. “So the Bird went back to his secret nest and this bird shone by my side through the endless hours of an old man’s day. A touching picture, is it not?”

“And then …?”

“Every so often, when the mood would take me, I would have Perlman wheel me to where the nest was hidden. Naturally, I was careful not to let him see its precise location. Then I would commune with my little friend and we would relive great adventures together. You will, of course, have observed precisely what species of bird this is, Mr. Watson?”

He held it up for my inspection and for a moment the sunlight breaking through the roof of palm leaves seemed to set it on fire, so that it blinded me.

“A phoenix, Mr. Watson. The supreme bird of fable that springs forth in various cultures that are otherwise quite unrelated. The Egyptians claimed it. So did the Arabs, the Indians, even the Chinese in their time. It clearly symbolizes something fundamental in human nature.”

Now my memory dredged up the reference.

“Isn’t that the bird that’s supposed to come out of the fire?”

“Correct. The phoenix lives its given span of years, as we all do, then it makes its nest, sings a melodious dirge—which, alas, few of us manage to do!—then flaps its wings to ignite the pyre and burns itself to ashes. And then the miracle occurs. The bird is reborn from the flames to start the cycle all over again. And perhaps that is the secret of its attraction. We would all like to be the phoenix—some of us more than others.

“But I fear an old man is wandering into the byways of philosophy. Yesterday I had Perlman take me to Shangri-La—only to find the Bird had flown … And that is why I have sent for you, Mr. Watson. Return my bird to me and you will find me a most grateful client. Now, what more do you need to know?”

“Who else lives here, Mr. Kane? Who else might have had access to the Bird?”

Out of the corner of my eye I saw Holmes nod his approval.

“Apart from my secretary and amanuensis, Perlman, whom you met, there is Kai-Ling, my man servant, a fairly recent acquisition. It was he who conducted you here.”

Charlie Chan. Right.

“There are the usual menials who come and go on a daily basis. Only Mrs. Chilvers, the housekeeper, lives in. And then, of course, there is my daughter, Nana. She is my only family …”

Then, as if anticipating my next question, he added— “I would rather you did not bother her. She has not been well and is easily upset. I have not told her the news yet. She will worry excessively on my behalf. We are very close. No, Mr. Watson, if you will take my advice, you will start your inquiries with the man who made me my replica. He has his ear to the ground—or should I say the underground. If someone is attempting to sell the Bird, Quentin Mallory will undoubtedly hear of it. Perlman can give you his address, as you leave.

“And now, Mr. Watson, I’m afraid all this talk has rather tired me. I am not normally so garrulous but catch a zealot on the topic of his religion and …” He gave a minimal shrug and what might have been a smile in my general direction.

Just behind him I saw Holmes nod, as if to say we had learned as much as we were likely to on this first interview.

I rose to my feet. Since Kane had both hands occupied holding and stroking his clone bird, I didn’t offer him mine. He seemed to have fallen back into his reverie but, as I moved back into the jungle, I heard him say—

“You may contact me at any time through Perlman, Mr. Watson, and he will take care of the usual arrangements. Since we cannot have Sherlock Holmes, I am trusting you to act in loco parentis. I wish you ‘Good hunting!’”

Holmes and I now repeated the decontamination process in reverse. No sooner had the inner door of the antechamber hissed to behind us than the outer door swung back to reveal the inscrutable Kai-Ling. It was as if he had been monitoring my every move—which he probably had. With an inclination of the head he led me back by a quite different route, which only confirmed my suspicion that on the way in we had been given the runaround—or at least the walk-around—to soften me up for my meeting with his employer.

It was as well that on the return trip he appeared to have run out of either guile or patience, for two things happened that we might otherwise have missed. At the head of a small staircase hung a large portrait. Kai-Ling would have hurried me on but I insisted on stopping to study it and there was little he could do about it, short of being downright rude and the Chinese haven’t yet figured out how to compete with the West in a way the West chooses to understand.

It was Holmes who gave me the idea, to be honest, when I saw him hovering around it. It was of a man in early middle age. He was standing in what was clearly hunting gear with a rifle over one shoulder. In the other hand he held a brace of dead game birds of some sort. The setting looked somehow European but the artist had provided no background clues to put it anywhere specific.

The man’s face was handsome in an aquiline sort of way but the eyes had an unsettling expression in them and the mouth was a thin line turned down at the edges. You would not wish to meet him on a dark night unless you knew for sure that he was on your side and had a signed affidavit to prove it.

“So our friend was Herne the Hunter before he became St. Francis of Assisi?” I heard Holmes say. “Presumably a conversion on the road to some Damascus?” I was about to reply when I saw tha

t Kai-Ling had fixed his gaze upon me.

I already had the impression that he had not formed too high an opinion of my capabilities and the sight of me talking to myself would do little to change that perception. It could wait until we were outside.

The second event occurred as we turned a corner into the entrance hall. Perhaps because we were returning by a different route, we took them by surprise but clearly the two people standing there hadn’t heard us approach. A man and a woman were standing there, engaged in what I can only describe as a lively difference of opinion. To be brutally frank, she was giving him not merely a piece of her mind but most of it. He wasn’t liking it one bit and he began liking it a lot less when he saw that we were witness to it.

The man was our old friend The Man in the White Suit and obviously not the same white suit since there was not a mote of dust to be seen within a mile. He could have posed for the ‘After’ in a detergent commercial and cleaned up in more ways than one.

The lady was our old friend’s old friend from yesterday. This I could deduce from the large floppy white straw hat she was wearing that once again shielded her face. Today she was wearing another floaty, pastel Laura Ashley number that also covered her from wrist to neck.

Perlman said something to her and she looked instinctively in our direction. I saw a beautiful sculpted face, the nose strong and straight, the mouth firm. But the thing I saw most was fear. It was the face of a frightened fawn. This woman was not just frightened to see me, a stranger in her home. She was frightened of much more. What with Perlman scooting off yesterday like the White Rabbit and now a nervous Nana, that made two in a row.

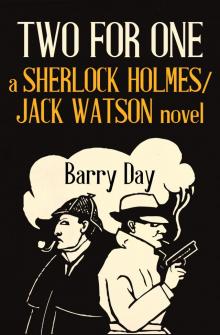

Two for One

Two for One Sherlock Holmes and the Alice in Wonderland Murders

Sherlock Holmes and the Alice in Wonderland Murders Sherlock Holmes and the Seven Deadly Sins Murders

Sherlock Holmes and the Seven Deadly Sins Murders P.G. Wodehouse in his Own Words

P.G. Wodehouse in his Own Words Sherlock Holmes and the Apocalypse Murders

Sherlock Holmes and the Apocalypse Murders Sherlock Holmes and the Shakespeare Globe Murders

Sherlock Holmes and the Shakespeare Globe Murders